Guayaquil, January 15th 2021

CNP-2021-309

Mrs.

Zanny Minton Beddoes

Editor In Chief

The Economist

1-11 John Adam Street

Westminster, London, England

The purpose of this letter is to address the misinformation in the article «Ecuador, a victim of illegal fishing, is also a culprit» published by The Economist on November 21, 2020 (https://www.economist.com/the- americas / 2020/11/21 / ecuador-a-victim-of-illegalfishing-is-also-a-culprit)

We regret that the article referring to fishing activities in Ecuador has presented a distorted overview of the work carried out by different public and private actors in our country for responsible fishing.

The article is a distorted view from NGOs’ spokespersons, who together with other groups worked to discredit the Ecuadorian fisherman during 2020, motivated by agendas of conservation groups financed by the NGO ISLAND CONSERVATION that seeks an expansion of the Galapagos Marine Reserve, which currently has 133,000 Km2, within the Ecuador’s EEZ.

Illegal fishing is a global concern that the Ecuadorian fishing sector is committed to combat due to the environmental and socio-economic importance of this productive sector that employs hundreds of thousands of people in Ecuador.

The country, after an intensive participatory legislative process that started back in 2015, passed in 2020 a new Act for the Development of Fisheries and Aquaculture, that incorporates new management tools to strengthen sustainable fisheries and combat IUU fishing. Along these lines, the new law includes dissuasive sanctions to discourage IUU fishing with fine amounts depending on the infraction that can go up to 1,500 “Unified Basic Salaries” (Salarios Básicos Unificados in Spanish), currently equivalent to US$600,000) with multiplying factors for recidivism that can take up to US $ 3,000,000, in addition to mechanisms for suspending and canceling fishing permits.

The referred article does not cite, for example, that NOAA’s 2019 report concludes that “on the basis of the information provided, NMFS has determined that the Government of Ecuador has taken appropriate corrective action to address the IUU fishing activities for which it was identified in the 2017 Report. Based on this finding, NMFS has made a positive certification determination for Ecuador”, evidencing the work of the National Fisheries Authority to enforce fisheries regulations. In the same way, it is highlighted that none of the cases associated with the NOAA report have to do with cases of fishing of protected species or fishing in marine reserve areas, as it seeks to contextualize the statements in The Economist’s article.

In the same line, the government of Ecuador together with the European Commission’s DG MARE coordinates actions to overcome the observations made regarding the yellow card issued, of which one of the main ones was already achieved, in relation with an updated regulatory framework. As Ecuador’s fishing sector, we know that our country will emerge even stronger after all response actions to the observations made by DG MARE are implemented, in order to continue providing our production to the world.

On the other hand, the article mentions that since 2018 at least 136 Ecuadorian industrial ships have entered the Galapagos’ Marine Reserve, a public declaration that, despite our repeated request, the Director of the Galapagos National Park himself has not been able to support with documented evidence. The article ends with an unsubstantiated assertion that the expansion of the reserve is a measure that «would help the threatened yellowfin tuna population«, a specie that according to the latest IATTC stock assessment is in a sustainable exploitation level.

The article does not mention all the positive actions that the Ecuadorian fishing sector does for the sustainability of its resources, both coastal and highly migratory. For example: in 2016 we established the TUNACONS project, the largest tuna Fishery Improvement Project (FIP) in the Eastern Pacific Ocean (EPO), which also has the participation of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). This FIP works on the continuous improvement of responsible fishing practices to achieve Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) certification, such as training our fishermen in practices of releasing vulnerable species of marine fauna when there is an incidence with fishing activities. Various examples of this are documented on the website https://tunacons.org/goodpractices/.

Additionally, we have led the development and implementation in the EPO of biodegradable FADs, something that is already a reality in more than 40 vessels of the Ecuadorian tuna fleet.

Our tuna fleet, together with the rest of the vessels that operate in the EPO, are the only fleets of tuna that fulfill a total closure of 72 days, in addition to an exclusive protection zone within the area between coordinates 96o N 110oW and between 4oN and 3oS called

“corralito” where fishing activity is prohibited for an additional 30 days period to safeguard the reproduction of tuna in the EPO. We are the only tuna fishery that does not carry out transshipments on high seas, precisely as a measure to combat illegal fishing and the excessive exploitation of natural resources, as well as a ban on discards, measures that do not occur in any other ocean of the world where other countries operate and where there is evidence of unsustainable practices and questionable labor practices that can even become slavery at sea.

Likewise, in Ecuadorian coastal fisheries there are various initiatives for sustainability in which the private and public fishing sector work with NGOs such as WWF, SFP, Conservation International and development agencies such as UNDP, in projects such as Coastal Fisheries Initiatives and Global Marine Commodities.

Ecuador, since 2006 has a National Action Plan for the Conservation of Sharks and Rays twice times evaluated and updated, being a regional and world reference.

Fishing of all turtle and whale species and other mammals is permanently prohibited in Ecuadorian waters, as well as the capture of giant manta rays (Manta birostris), Mobula japonica, M. thurstoni, M. munkiana, and M. tarapacana, whale sharks (Rhincodon typus), basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus), great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) and sawtooths (Pristis spp). There is an extensive National Plan of Action on the Conservation of Marine Turtles, published in 2014, which includes measures to reduce the impact of fisheries on the five turtle species present in Ecuadorian waters. There is also a National Plan of Action for Sharks in force since 2006.

Also, there are regulations about marine mammals, sharks and marine turtles’ species:

- The Organic Law for the Development of Aquaculture and Fisheries of Ecuador establish: o Article 213 establish as a serious fishing infraction to carry out intentional interaction in fishing activities with marine mammals, sea turtles or whale http://camaradepesqueria.ec/wpcontent/uploads/2020/04/Ley–de–Acuicultura–y–Pesca–2019.pdf

o Article 152 establish the prohibition of the targeted fishing of sharks, mantas and other elasmobranchs that the governing Authority may determine, as well as the manufacture, transport, import, commercialization of fishing gear used to capture these resources, the mutilation of shark fins and the discard of their bodies to the sea, the importation, transshipment and internment of whole sharks or shark fins in any state of conservation or processing, even when they have been caught in international waters. http://camaradepesqueria.ec/wp–content/uploads/2020/04/Leyde–Acuicultura–y–Pesca–2019.pdf

• National Plan for marine turtles’ conservation, Ministerial agreement 304. October, 2014. https://www.derechoecuador.com/registro–

oficial/2014/11/registro–oficial–no–371—lunes–10–de–noviembre–de–2014suplemento

- Protection of whales: Ministerial Agreement 196 Official Registry 458 of June 14, 1990. http://acuaculturaypesca.gob.ec/wpcontent/uploads/2018/03/3–ACUERDO–196–BALLENAS–RO.pdf

- National plan of action for the conservation, sustainable management, and recovery of the populations of sharks, rays, guitars and chimeras found in the Ecuadorian maritime territory https://www.wwf.org.ec/bibliotecavirtual/publicacionesec/?uNewsID=364 191

- Species around the Galapagos Islands are protected by the 133 thousand square kilometers Galapagos Marine Reserve, established in 1998 as an area completely closed to industrial fishing. Although the majority of the area is exclusively open to Galapagos artisanal fishing (large pelagic, crustacean and demersal species), there are also several substantial notake zones.

All these actions are a small sample of all the good practices implemented by Ecuador for responsible fishing in a sector that is fundamental for the socio-economic development of our country, which despite the limitations of a developing economy, has always worked hard to be a world reference in the fishing field.

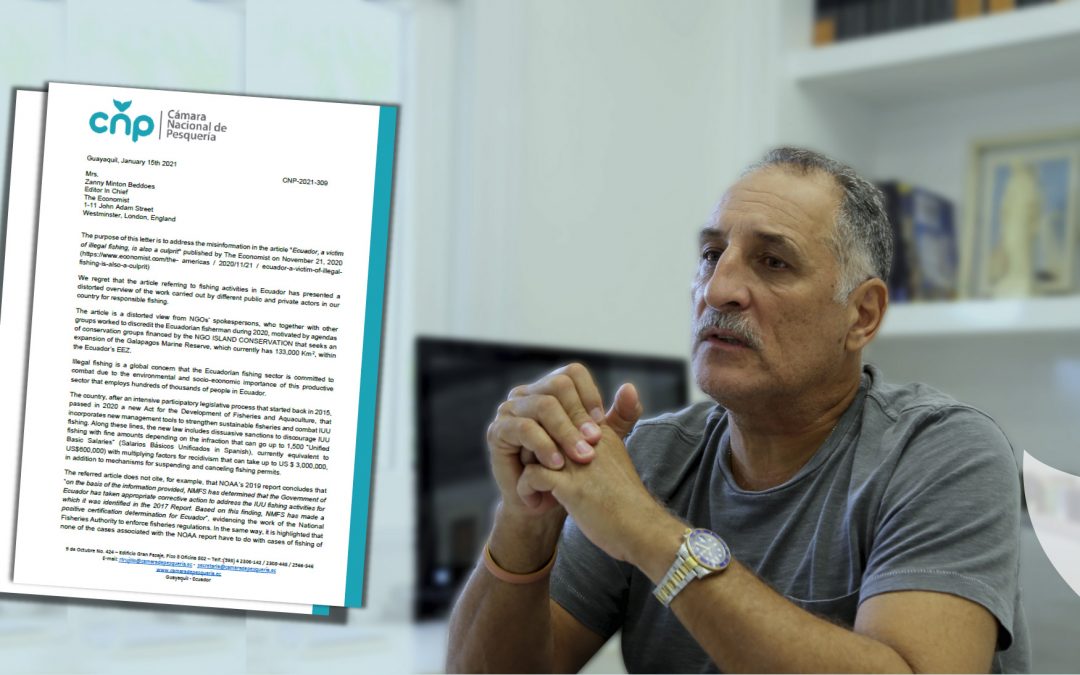

To conclude, even though I was interviewed by The Economist journalist Mariana Palau, most of our statements were not included in the referred article. Therefore, as National Chamber of Fisheries we request that this letter be replicated through an article or journalistic investigation in which the information can be expanded to correct the misinformation.

Best regards,

Bruno Leone

President

National Chamber of Fisheries